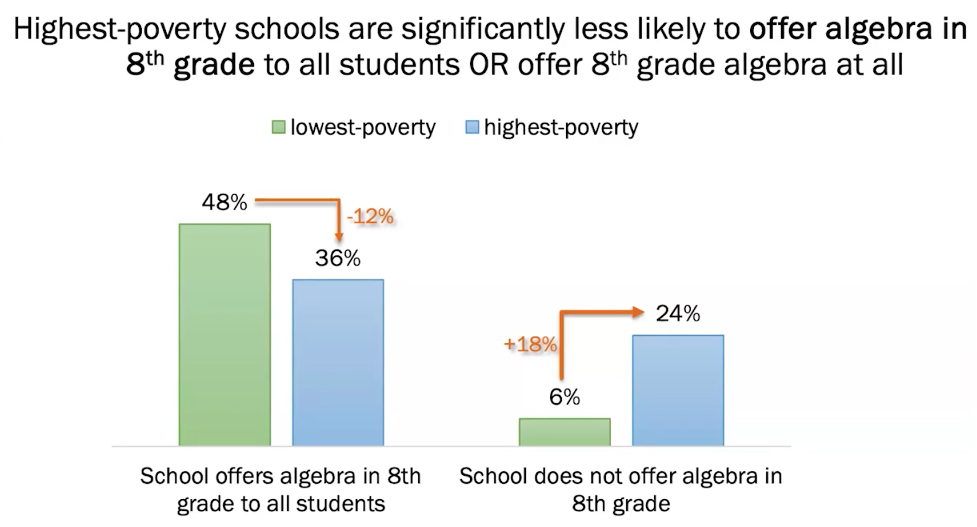

Conversely, poor schools are much less likely to adopt an algebra-for-all policy for eighth graders. Nearly half of the richest schools offered algebra to all of their eighth graders, compared with about a third of the poorest schools.

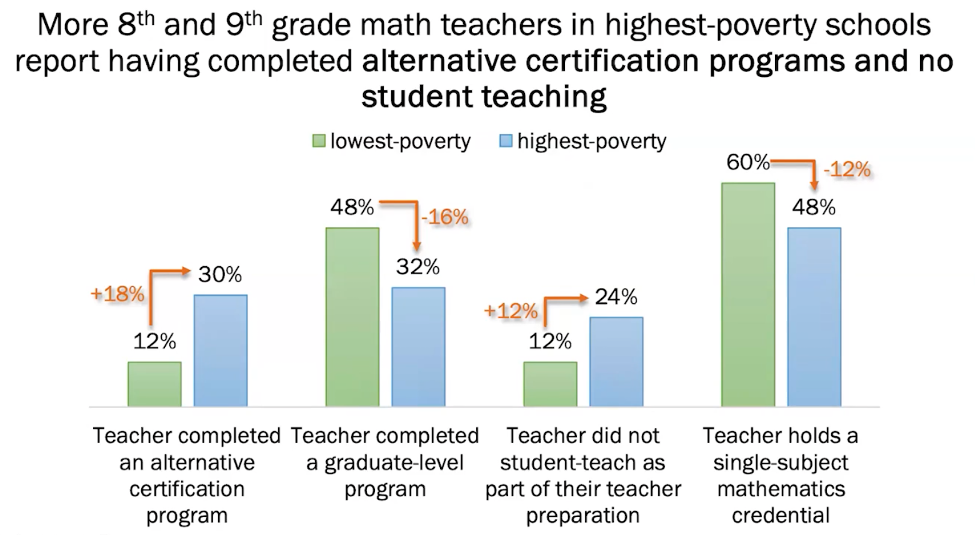

Mathematics teachers in high-poverty schools tend to have lower professional preparation. They were much more likely to have entered the profession without first earning a traditional teaching degree from a college or university, but rather by completing an alternative on-the-job certification program, often without students having to teach under supervision. And they were less likely to have an advanced degree or a math degree.

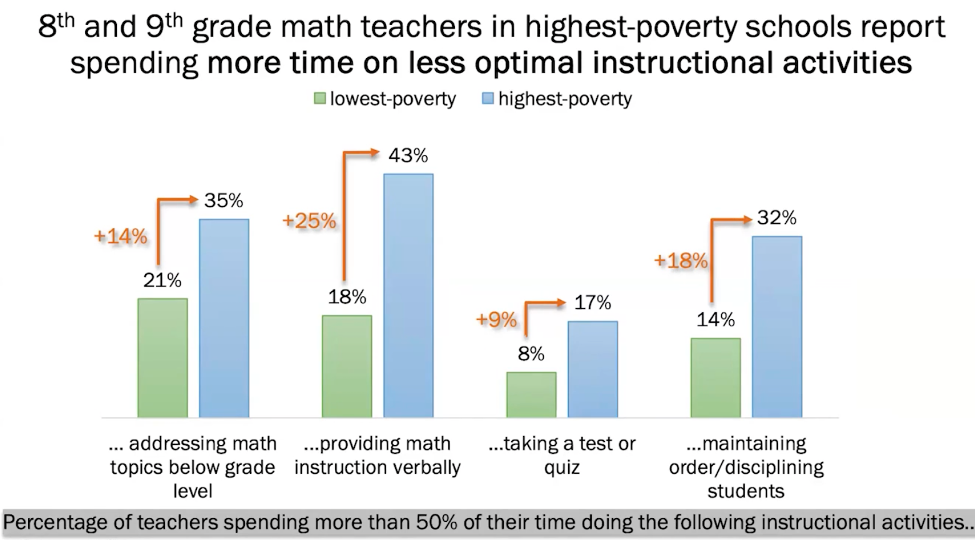

In surveys, a third of math teachers in high-poverty schools reported that they spent more than half their classroom time teaching topics that were not at grade level, as well as managing student behavior. students and to discipline students. Lecture teaching, as opposed to classroom discussions, was much more common in poorer schools than in wealthier schools. RAND researchers also detected similar gaps in teaching models when they examined schools along racial and ethnic lines, with black and Hispanic students receiving “less optimal” instruction than white students. But these gaps were larger by income than by race, suggesting that poverty may be a more important factor than prejudice.

Many communities have tried enrolling more eighth-graders in algebra classes, but that has sometimes made matters worse for unprepared students. “Just giving them an eighth-grade algebra course is not a silver bullet,” said AIR’s Goldhaber, who commented on RAND’s analysis during a Nov. 5 webinar. Either the material is too demanding and students are failing, or the course was “algebra” in name only and didn’t really cover the content. And without a college preparatory pipeline of advanced math courses to take after algebra, the benefits of taking Algebra 1 in eighth grade are unlikely to multiply.

It is also not economically practical for many low-income colleges to offer an Algebra 1 course when only a handful of students are advanced enough to take it. A teacher would need to be hired for even a few students and those resources could be spent more efficiently on something else that would benefit more students. This particularly disadvantages the most advanced students in low-income schools. “It’s a difficult problem for the schools themselves to solve,” Goldhaber said.

Improving the quality of mathematics teachers in the poorest schools is a crucial first step. Some researchers have suggested paying good math teachers more to work in high-poverty schools, but that would also require renegotiating union contracts in many cities. And even with financial incentives, there is a shortage of math teachers.

For students, AIR’s Goldhaber argues that the time to intervene in math is in elementary school to ensure that more low-income students have strong foundational math skills. “Do it before college,” Goldhaber said. “For many students, college comes too late. »

This story about eighth grade math was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger reportan independent, nonprofit news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Register for Proof points and others Hechinger Newsletters.