by Terry Heick

How do you know if a student really understands something?

They learn very early on to play the game – contest the teacher and / or the test what they “want to know” and even the best evaluation leaves something on the table. (In truth, a large part of the time that students simply do not know what they do not know.)

The idea of understanding is, of course, at the heart of all learning and resolving it as a puzzle is one of the three pillars of formal learning and education environments.

1. What do they need to understand (standards)?

2. What (and how) currently understand (evaluation)?

3. How can they better understand what they are not currently doing (planning learning experiences and instructions)?

But how do we know if they know it? And what is “that”?

Understanding like ‘He’

On the surface, there are problems with the word “IT”. It seems vague. Embarrassing. Uncertain. But everyone knows what it is.

“This is essentially what must be learned, and it can be a frightening thing for teachers and students. “It is”, described with intimidating terms such as objective, target, competence, test, examination, note, failure and success.

And in terms of content, “that” could be almost anything: a fact, a discovery, a habit, a competence or a general concept, from mathematical theory to a scientific process, the importance of a historical figure to an objective of an author in a text.

So if a student gets it, beyond pure school performance, what could they do? There are many taxonomies and existing characteristics, from Bloom to understanding through design 6 facets of understanding.

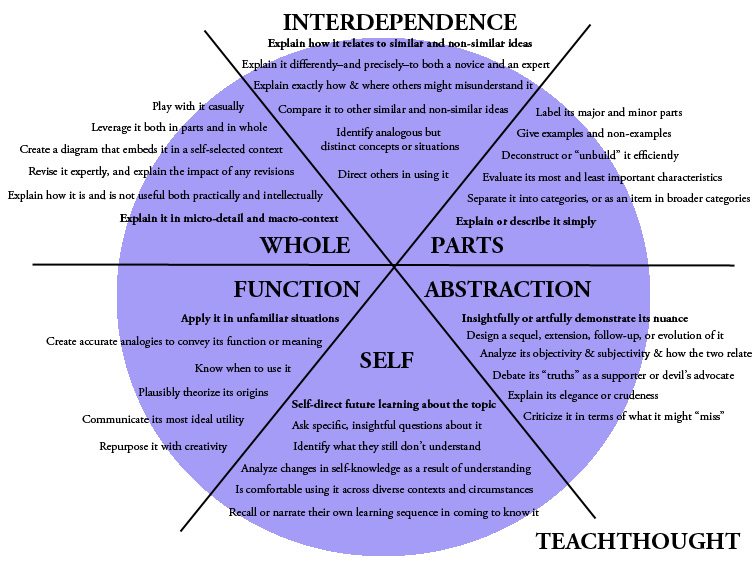

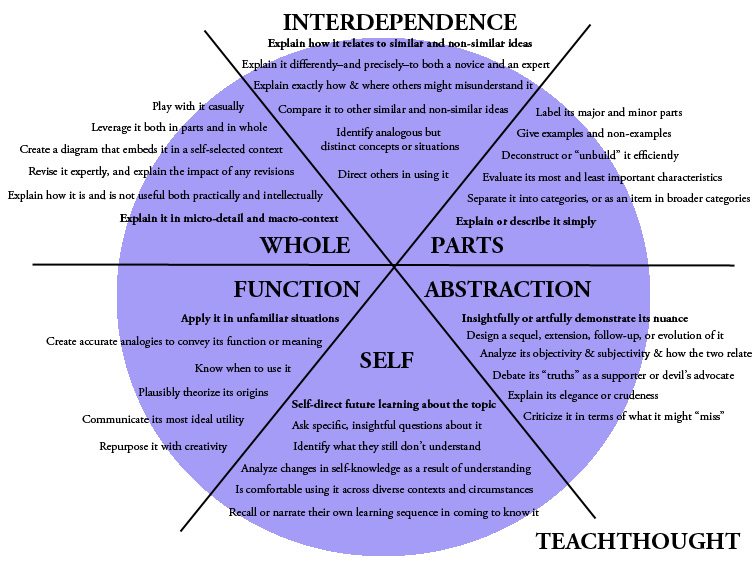

The following actions are configured as a linear taxonomy, from the most elementary to the most complex. The best part on this subject is its simplicity: most of these actions can be carried out simply in class in a few minutes and do not require complex planning or an extended examination period.

Using a quick diagram, a conceptual card, a T graph, a conversation, an image or a short response in a newspaper, a fast face -to -face collaboration, on an output slip or via digital / social media, understanding can be evaluated in a few minutes, helping to replace tests and dismay with an assessment climate. It can even be displayed on a class website or hung in class to help guide autonomous learning, students verify for understanding.

How does this understanding of taxonomy work

I will write more about this soon and I soon put it in a more graphic form; Both are essential to use it. (Update: I also create a course so that teachers help to use it.) For the moment, I would say that it can be used to guide planning, evaluation, curriculum design and autonomous learning. Or to develop Critical thinking questions for any field of content.

The “Heick” learning taxonomy is supposed to be simple, organized as (mainly) isolated tasks which vary in complexity less to more. That said, students do not need to demonstrate the levels of “highest” understanding – which lack the point. Any ability to accomplish these tasks is a demonstration of understanding. The greatest number of tasks that the student can accomplish, the better it is, but all the “checked boxes” are proof that the student “obtains”.

36 thinking strategies to help students fight with complexity

Heick learning taxonomy

Domaine 1: parts

- Explain it or simply describe it

- Label its major and minor parts

- Evaluate its most and less important characteristics

- Deconstruct or “get rid” effectively

- Give examples and non-examples

- Separate it into categories or as an element in wider categories

Subject example

Revolutionary war

Introductory examples

Explain the revolutionary war in simple terms (for example, an inevitable rebellion which has created a new nation).

Identify the major “parts” of the revolutionary war (for example, the economy and propaganda, soldiers and prices).

Evaluate the revolutionary war and identify its least important and most important characteristics (for example, caused and effects compared to the names of the city and minor skirmishes)

Domaine 2: All

- Explain it in micro-detail and macro-context

- Create a diagram that integrates it into a self-selected context

- Explain how it is and is not useful both practically and intellectually

- Play with

- Take part in part and as a whole

- Revise it expertly and explain the impact of any revision

Domain 3: Interdependence

- Explain how it relates to similar and non -similar ideas

- Direct the others to use it

- Explain it differently – and precisely – both a novice and an expert

- Explain exactly how and where others could understand it badly

- Compare it to other similar and non-similar ideas

- Identify ideas, concepts or similar but distinct situations

Domain 4: the function

- Apply it in unknown situations

- Create specific analogies to transmit its function or meaning

- Analyze the ideal point of its utility

- Reuse it with creativity

- Know When To use it

- Plausibly theorize its origins

Domaine 5: Abstraction

- Demonstrate its nuance in a personal or artistic way

- Criticize him in terms of what he could “miss” or where he is “dishonest” or incomplete

- Debate his “truths” as a supporter or defender of the devil

- Explain his elegance or coarseness

- Analyze its objectivity and subjectivity, and how the two relate

- Design a sequel, an extension, a follow -up or an evolution

Domaine 6: The Self

- Autonomous future learning on the subject

- Ask specific and insightful questions about this

- Remember or tell their own learning sequence or chronology (metacognition) to know it

- Is comfortable using it in various contexts and circumstances

- Identify what they still don’t understand

- Analyze changes in self -knowledge following understanding

Advanced understanding

Understanding the 6 facets of understanding the design, bloom taxonomy and the new Marzano taxonomy have also been referenced in the creation of this taxonomy; learning taxonomy for understanding

Founder and director of teaching