The national evaluation of educational progress (NAEP), which provides data for the Nation Bulletin, is mandated by Congress and is the largest representative test at the national level of student learning. NAEP tests were administered for the first time in 1969. Today, mathematics and reading assessments are given every two years to a large sample of students in fourth and eighth year.

Students remained stable in mathematics or even invented

In the fourth year, the average mathematical score has slightly checked compared to 2022, ending a pandemic slide. In fact, white, black, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students have all shown modest gains, on average.

“In the fourth year, it seems that, no matter where the students were, they improved,” explains Lisa Ashe, mathematics consultant to the Department of Public Education of North Carolina and member of the Board of Directors national evaluation, which establishes the NAEP policy.

That said, the fourth year mathematical scores have remained below Pre-Pandemic Levels of 2019, with one exception: Alabama was the only state where the average mathematical math scores of fourth-year students exceeded 2019 scores (in 2022, legislators adopted a law aimed at improving control Mathematics for all kindergarten students in 5th place in the state.)

But Covid-19 is not all to blame. A longer vision of the mathematical scores of fourth year – and the success of students more broadly – shows that these scores have started stagnating and even decreasing Before The pandemic. Mathematical scores culminated around 2013. Several education researchers tell NPR that they don’t know why.

“This is the question of several dollars of several dollars,” explains Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the University of Washington who studied the loss of pandemic learning.

One thing we know is that fourth year mathematical performance has improved roughly at the same time when the old federal education law known as No Child Left Behind (signed in 2002) applied new strict strict requirements. When these requirements were deleted (from 2012) and finally replaced (in 2015), mathematical performance, especially among the performance, fell.

This is only a possible explanation for the slowdown that the pandemic has aggravated. Goldhaber suggests that learning could also have been fell by the great recession, through increased access to smartphones and children’s tablets or by the training effects of a reduction in children’s reading for pleasure. (Since 2017, fewer and fewer students have reported to Naep that they like reading.)

“It is important to understand what caused this previous stagnation if we want to get out of the mud of the pandemic,” explains Goldhaber.

For the eighth year students, mathematical scores remained stable in 2024 compared to 2022. But as with the fourth year students, they remained below the 2019 pre-pale levels.

In addition, the country’s bulletin highlights a disturbing divergence that occurs in these scores. The most efficient eighth year students improved In mathematics compared to 2022, but the least efficient students moved in the opposite direction, losing ground in 2024.

“It actually caused an alarm,” said Ashe about the widening of the success gap. “We must meet the needs of these students who are in the lower centiles, because something we do is not working for these students.”

Overall, 39% of fourth year students and 28% of students in the eighth year obtained a score to the NAEP maturation standard or above. It is a little better than in 2022.

The NAEP report warns against the comparison of these results to numbers declared by the State, because “the NAEP standard for competence represents competence on the difficult subject, a standard which exceeds the standards of most states for a competent or educational level. “

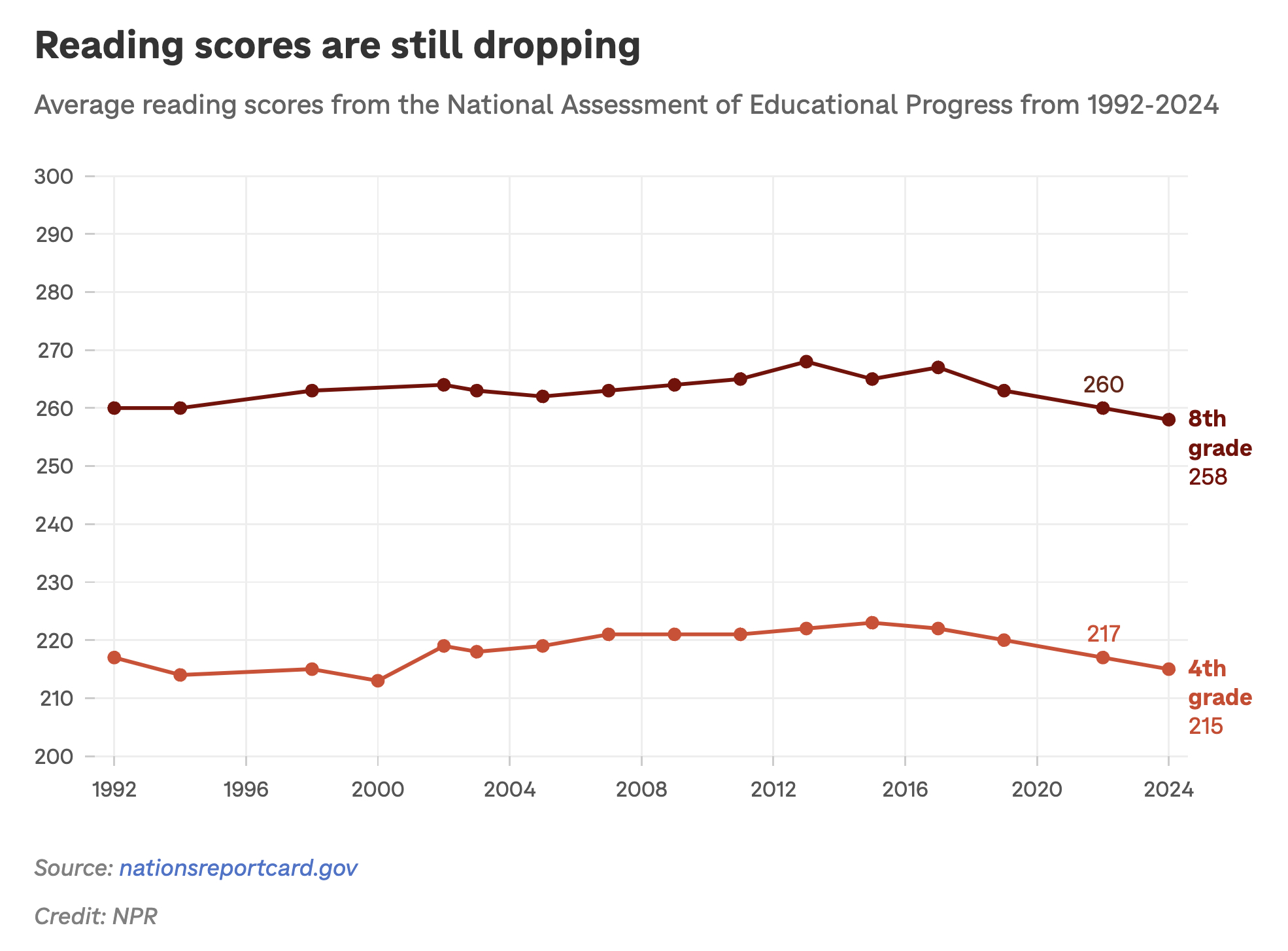

Reading: Bad news has worsened

The results of the reading were not as full of hope as in mathematics:

Fourth year students continued to lose ground in 2024, with slightly lower reading scores, on average, in 2022 and much lower than what they were in 2019.

In 2019, 35% of fourth year students obtained a score with the standard of reading competence or above the test.

This figure fell to 33% in 2022 and, moreover, 31%, in 2024.

As with mathematics, these drops are not entirely the fault of the pandemic. The fourth year reading scores began to fall for years earlier, around 2015.

Only one state, Louisiana, saw its fourth year reading scores in 2024 exceed 2019 scores.

It should be remembered: this current series of fourth year students, from the 2023-2024 school year, was in kindergarten when the pandemic closed schools, and many spent part of the first year to learn from a distance.

The reading scores of eighth year students in 2024 also dropped compared to 2022, with only 30% of students performing or above the competent standard of NAEP.

NAEP classifies students to one of the three skill levels: advanced, competent or lowest, basic. According to the results, the share of reading the eighth year students below NAEP’s basic standard “was the most important in the history of evaluation”.

Not only that, but the less efficient readers in 2024 marked “less than our lower artists 30 years ago for the fourth And eighth year. This is how these scores have dropped historically, ”explains Peggy Carr, Commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics.

No state has improved its eighth year reading scores compared to 2022, not to mention 2019.

The link between poverty and performance

The results of this year’s NAEP include a new, more precise index to determine the socio -economic status of students (SES), and the results show, in detail, what teachers and researchers have long understood: that poverty and performance are deeply connected.

For example, the overwhelming majority (77%) of fourth year students in the highest SSE category – the richest children – took place above the national reading average.

Among the fourth year students in the lowest SSE category, however, the results are almost returned, with only 34% occurring above the national average.

The results of mathematical performance was also disparate.

On a positive note, while many districts of big cities have achieved major gains in fourth -year mathematics with their economically disadvantaged students, a handful of districts have made exceptionally Well, including the Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools in North Carolina, the schools of the county of Guilford (also in North Carolina), the public schools of Baltimore City and the San Diego Unified School District.

The missing school discomforts learning

When the students made the latest NAEP assessments at the beginning of 2024, they were asked how many days they had been absent the previous month. The results are slightly encouraging: a smaller percentage of fourth and eighth year students said that he had missed five days or more schools in the last month compared to 2022.

But in all areas, less -efficient students were more likely to report the missing five or more school days the previous month compared to more efficient students.

In other words, the missing school means missing learning.

When students are missing 10% or more than a school year, they are considered “chronic absent” and, as NPR previously reported, chronic absenteeism rates doubled during the pandemic.

The link that Naep shows between the missing school and the lower school realization does not surprise Hedy Chang, responsible for attendance works, an organization devoted to the fight against chronic absenteeism. “This has not only affected academics,” she said about absenteeism. “This affects social development and executive functioning.”

To continue on the path of improving attendance and, in turn, the success of students, Chang suggests that the districts look at the students who are missing the most school and the obstacles they face.

“You might not be able to take everything, tackle suddenly,” says Chang. “You may need to attack it in pieces, either by barrier or by grade or by this subset of schools.”