by Terry Heick

I first learned about the 40/40/40 rule years ago while reading through one of those giant (and indispensable) 400-page Understanding by Design tomes.

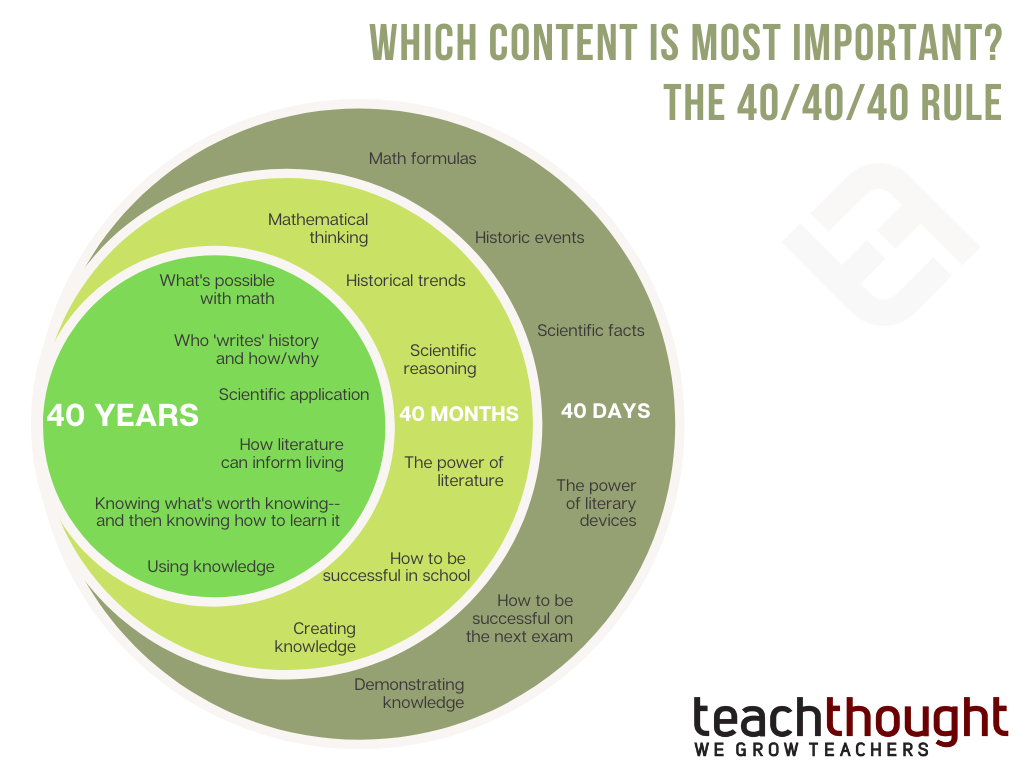

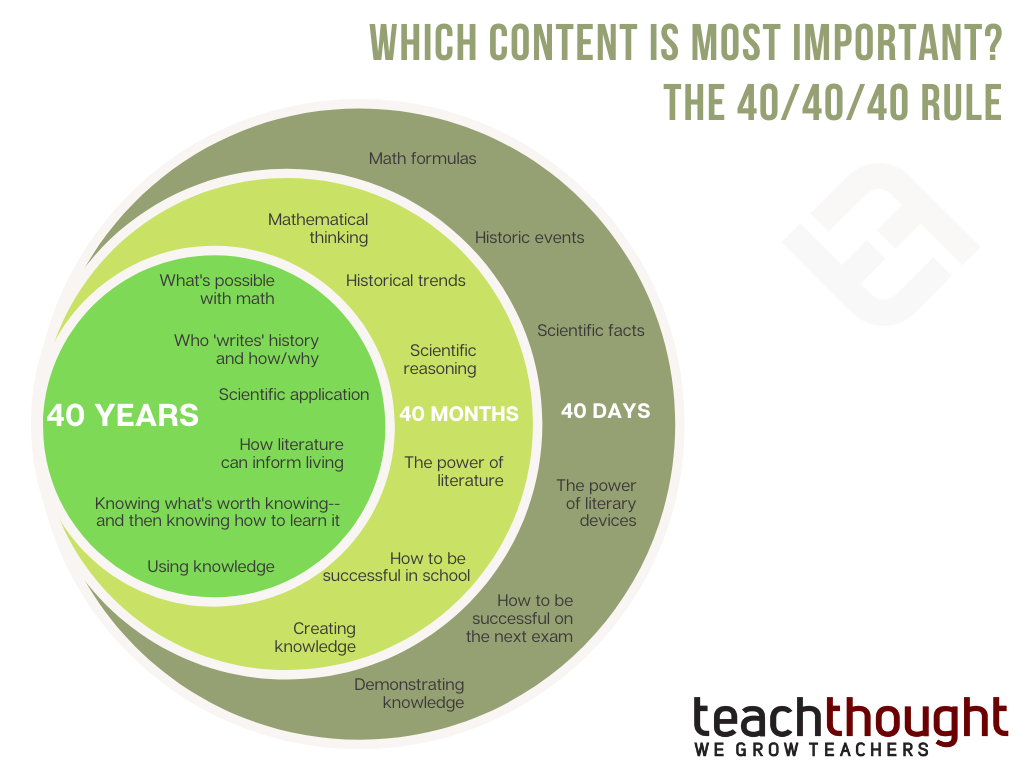

The question was quite simple. Of all the academic standards, you are responsible for “covering” (more on that in a minute) what is important for students to understand over the next 40 days, what is important for them to understand over the next 40 months and what is important for them to understand. understood for the next 40 years?

The 40/40/40 Rule: Prioritizing Long-Term Value in Teaching

In the changing educational landscape, teachers often wonder about the long-term impact of their daily teaching. The 40/40/40 rule provides a framework for ensuring that the content we teach is of lasting importance, not only in the immediate context of the classroom, but also in the broader context of students’ lives.

The 40/40/40 rule serves as a guiding principle for evaluating the relevance of educational materials over three distinct time periods:

The next 40 days: This deadline represents the immediate application of the content. This encourages teachers to think about what students need to know now to succeed in future lessons, units, or assessments. By focusing on this short-term value, teachers ensure that students have the foundational knowledge essential for immediate academic progress.

The next 40 months: Extending beyond the immediate future, this phase encourages educators to assess what skills and knowledge will remain relevant as students progress through subsequent grades and educational stages. Content selected from a 40-month perspective supports continuity of learning, establishing a solid foundation for future academic challenges and interdisciplinary applications.

The next 40 years: The final level emphasizes lifelong learning and the wider applicability of knowledge. Here, the goal is to prioritize skills and concepts beyond the classroom (critical thinking, problem solving, and adaptability) that students will carry with them throughout their adult and college lives. their professional landscape. This perspective ensures that educational experiences contribute significantly to the development of thriving, lifelong learners.

The 40/40/40 rule challenges us to align our teaching with these overlapping timelines, moving beyond short-term gains and instead focusing on building a curriculum that balances immediate relevance and lasting value. When applied consistently, this framework encourages educational choices that serve students as learners and future members of society.

Of course, this leads us to discuss both power norms and enduring understandings, curriculum mapping, and instructional design tools that teachers use every day.

But it got me thinking. So I drew a quick pattern of concentric circles – something like the image below – and started thinking about the writing process, tone, symbolism, audience, purpose, structure , word parts, grammar, and a thousand other elements of ELA.

No (necessarily) power standards

And it was an enlightening process.

First, note that this process is a little different from identifying power standards in your program.

Power standards can be chosen by examining those standards that can serve to “anchor and integrate” other content. This idea of “40/40/40” is more about being able to look at a lot of things and immediately spot what is needed. If your house is on fire and you have 2 minutes to do what you can do, what do you take with you?

In a way, this can be reduced to an argument between depth and breadth. Hedging versus control. UbD refers to it as the difference between “nice to know,” “important content,” and “lasting understanding.” These labels can be confusing: Sustainable vs. 40/40/40 vs. Power Norms vs. Big Ideas vs. Essential Questions.

That’s why I loved the simplicity of the 40/40/40 rule.

It occurred to me that it was more about contextualizing the child in the middle of the content, rather than just unpacking and organizing the standards. One of the UbD framing questions for establishing “big ideas” provides some clarity:

“To what extent does the idea, topic, or process represent a “big idea” with lasting value beyond the classroom?

The essence of the 40/40/40 rule seems to be to honestly examine the content we provide to children and contextualize it in their lives. This hints at authenticity, priority, and even the kind of lifelong learning that teachers dare to dream of.

Applying the 40/40/40 rule in your classroom

There’s probably no one “right way” to do this, but here are some tips:

1. Start alone

Even though you’ll soon have to socialize them with team or department members, it’s helpful to clarify how you feel about the program before the world joins you. Additionally, this approach forces you to analyze the standards closely, rather than just being polite and nodding repeatedly.

2. Then socialize

After you sketch out your thoughts on the content standards you teach, share them – online, in a data team or PLC meeting, or with colleagues an afternoon after school.

3. Keep it simple

Use a simple 3 column chart or concentric circles as shown above and start separating the wheat from the chaff. No need to complicate your graphic organizer.

4. Be flexible

You will have a different sense of priority than your colleagues when it comes to standards. These are different personal philosophies about life, teaching, your content area, etc. As long as these differences are not drastic, it is normal.

5. Realize that children are not little adults

Of course, everyone should spell correctly, but weighing spelling versus extracting implied nuances or themes (typical English language arts content) is also about realizing that children and adults are fundamentally different. It’s rare that a child is able to examine a range of media, synthesize themes, and create new experiences for readers without being able to use a verb correctly. It can happen, but therein lies the idea of power norms, big ideas, and, most immediately, the 40/40/40 rule: one day – 40 days. In 40 months, or even 10 years, the students in front of you will be gone – adults in the “real world.”

Anything they can do – or cannot do – at that time will not be your fault, no matter how good the lesson, the assessment design, the use of data, pace guide or program map. But if you can accept that – and work backwards from the worst-case scenario – “if they don’t learn anything else this year, they’ll know this and that – then you can work backwards from those priorities.

These pieces of content that will last 40 years or more.

In your content area, on your curriculum card, pacing guide, or whatever guidance document you use, start by filling in this little orange circle and work backwards from there.

What content is most important? The 40/40/40 rule